ISLE DE JEAN CHARLES, La.—The Rev. Roch Naquin grew up on this island along the Louisiana coast, trapping muskrats and mink in the marsh beyond his family’s home and cutting firewood from a stand of oak trees.

The trees and the marsh are gone now, submerged under rising sea levels that have nearly engulfed the island, which has been home to the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw for generations. As the island slowly disappears, so, too, does the tribe’s way of life.

Isle de Jean Charles, a narrow strip of land about 90 miles southwest of New Orleans in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, has lost 98 percent of its landmass to rising waters of the Gulf of Mexico since 1955, when tracking began. An island that once encompassed more than 22,000 acres, now is only 320 acres. Scientists predict the island will disappear in 50 years.

In 2016, Louisiana’s Office of Community Development received $48 million from the Department of Housing and Urban Development to resettle current and former residents of Isle de Jean Charles, designating them the first federally funded climate migrants in the continental United States.

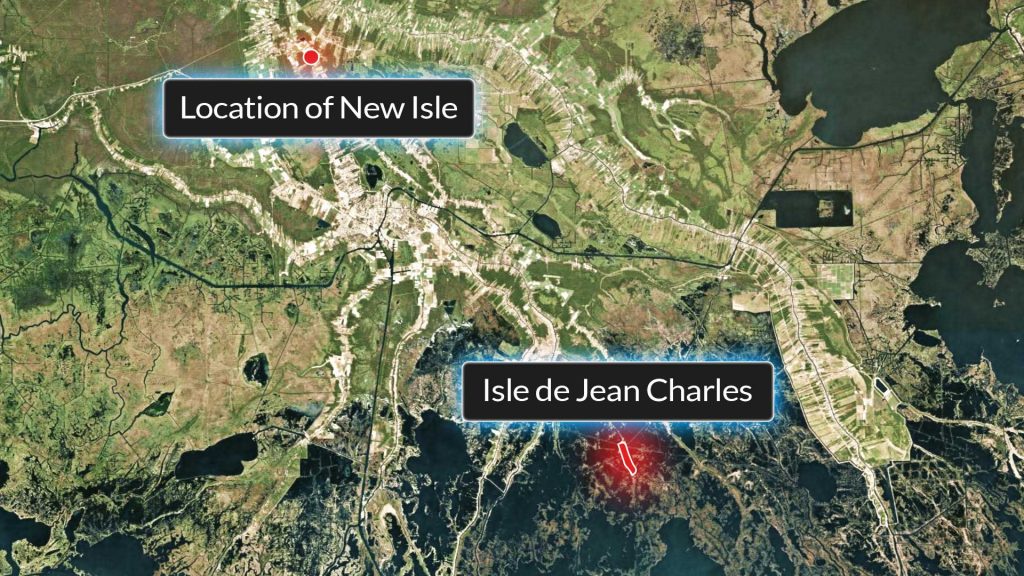

With construction now underway on a “New Isle”—a 515-acre sugarcane field 40 miles away—the resettlement stands as a case study of the powerful forces unleashed by climate change and the sensitivities involved when Indigenous people are encouraged to leave their ancestral homelands.

The Government Accountability Office in 2020 recommended that Congress establish a federally led pilot program to help communities interested in relocation based on the lessons learned from the Isle de Jean Charles relocation effort, which it said exhibited unclear federal leadership and coordination that contributed to a complex resettlement process “that may not meet the needs of the island’s residents.” The GAO also recommended that a federal agency like the Federal Emergency Management Agency or the Department of Housing and Urban Development be authorized to lead climate migration assistance in the future.

A HUD spokesman said that the Biden administration has proposed providing $100 million to Native American tribes “to increase energy efficiency, improve water conservation and further climate resilience,” and $2 billion to expand affordable housing and create “climate-resilient community development” in tribal communities.

“The Biden-Harris Administration is committed to strengthening Tribes’ climate resilience,” the spokesman said.

Several indigenous tribes nationwide will likely soon face the same choice as the Isle de Jean Charles tribal members—to flee or stay until the end as sea level rise, erosion and subsidence replace their lands with water. They are among an estimated 13 million Americans who could be displaced by 2100 as a result of sea level rise, 70 percent of whom will be in southeastern states like Louisiana, according to a study by University of Georgia demographer Mathew Hauer.

A combination of accelerating climate change, human activity and natural processes have caused the land loss in coastal communities like Isle de Jean Charles, said Alex Kolker, a coastal geologist at Louisiana Universities Marine Consortium, and other experts.

Landmass washed into the sea after oil and gas companies cut canals and built pipelines that destroyed freshwater wetlands. Levees and dams constructed on the Mississippi River obstructed the natural flow of water and sediment needed to build wetlands that protect coastal areas from storm surges and erosion.

Sea level rise is higher because of climate change and because the land is sinking quickly, both of which, in turn, strengthen storms. Sea levels in the Gulf Coast region rose five to six inches over the global average during the last century, according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Timelapse – Isle de Jean Charles is Disappearing (Medill News Service)

Louisiana Island Disappears into the Gulf

Hardest hit by climate displacement in the United States are Native American tribes, who often depend on traditional subsistence hunting and fishing and gathering. Not only does climate change threaten their ancestral lands, but also their way of life and culture. Lack of government response, especially for tribes not federally recognized, increases their vulnerability.

In 2020, five tribes from Alaska and Louisiana, including the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, submitted a complaint to the United Nations alleging that the U.S. government is violating their human rights by failing to address climate change impacts that result in forced displacement, placing them at “existential risk.”

Inaction on climate change has resulted in communities being broken apart and losing ancestral homelands, sacred burial sites, cultural traditions and heritage and livelihoods, the complaint said. While the government has known for decades that climate change threatens coastal tribes, it has failed to allocate resources to support the tribes’ community-led adaptation efforts.

“Despite their geographic differences, the tribes in Louisiana and Alaska are facing similar human rights violations as a consequence of the U.S. government’s failure to protect, promote and fulfill each tribe’s right to self-determination to protect tribal members from climate impacts,” the complaint said.

As Isle de Jean Charles residents prepare to move to new homes next winter, an international campaign gains momentum to make “ecocide”—severe and widespread or long-term environmental damage—a crime before the International Criminal Court in the Hague, alongside genocide, crimes againast humanity, war crimes and crimes of aggression.

While the campaign has no legal applicability to the relocation from Isle de Jean Charles—the United States is not among 123 member nations party to the court’s jurisdiction—a legal definition of “ecocide” recently put forth by a panel of lawyers has added moral salience to the debate about threats posed by climate change and polluting practices to Indigenous people around the world.

Should ecocide ultimately become the fifth international crime through a ratification process that could take years, Indigenous people forced off their land in numerous countries couldask the court’s prosecutor to hold government officials accountable for inaction on climate change.

On Isle de Jean Charles, a “Sense of Calm” Pervades

Isle de Jean Charles is in a part of Louisiana that was deemed “uninhabitable swamp land” by the state until 1876, when survivors of the Trail of Tears sought refuge there, living off trapping, fishing and agriculture. For generations, families planted traditional medicinal plants, corn, beans, carrots and mustard in their backyards. Those crops can no longer survive the increasing saltwater intrusion. Where they used to trap, they now use boats to fish.

Since the 1930s, Louisiana has lost 1,900 square miles of land, an area roughly the size of Delaware. Louisiana loses nearly 25 square miles of land annually, according to the Coalition to Restore Coastal Louisiana.

At its height, Isle de Jean Charles had 78 homes and 400 residents. With each battering hurricane, more families moved off the island to higher ground, losing connection to their land and people. After Hurricane Lili in 2002, there were 68 homes left. After hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, that number had shrunk to 54. And after hurricanes Gustav and Ike in 2008, 25 homes remained.

A sense of calm now surrounds the island, as if time moves slower and nothing bad happens there, despite remnants of disaster. A UFO-looking pod used to flee hurricanes. Pieces of a family home scattered across the yard.

Cracks that pierce the repeatedly flooded two-mile road running through the island, with misty blue waters dabbed with green marsh slowly creeping up on either side.

Families gather under their elevated homes next to trees that have died from saltwater.

Theo Chaisson, a store owner with photos behind his cash register of tribal members, family and boats he built, asked a regular customer on a recent afternoon how many trout he caught.

“There used to be land there” is a common saying as residents point to where they used to trap animals, walk to lakes and play soccer. Signs like “family home, not for sale” are posted outside the 25 colorful homes that remain, reminding visitors that the community wants to stay put, though many believe they should leave.

An eight-foot ring levee around the island helps reduce flooding from weaker storms, but it’s not high enough to protect against the more severe flooding that comes each storm season, bringing weeks on end of high water.

Rumors float through town that the community is being pushed out for wealthier recreational fishermen to create a “sportsman’s paradise.” Last year, the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries built five fishing piers with docks to make fishing safer for public access. This year, Terrebonne Parish elevated the road eight feet above sea level using 20,000 tons of large limestone rock to protect it from flooding and erosion, even though it had warned back in 2011 that the road would not be fixed in the future.

“They gonna take care of this island here, this island ain’t going nowhere,” said Chaisson, who has been nicknamed “mayor of Isle de Jean Charles.”

In 2002, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began planning the 72-mile Morganza to the Gulf levee system, designed to protect small bayou communities from flooding, but decided it would be too costly to include Isle de Jean Charles in the protective system.

After that, Albert Naquin, chief of the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw tribe, started planning a relocation for the community.

He is a descendant of Jean Charles Naquin, a Frenchman who arrived in Louisiana in 1785. Naquin had four children, including Jean Marie Naquin, who married a native woman and settled in the undeveloped marshland that would later become Isle de Jean Charles. Born in 1841, his son Jean Baptiste Narcisse Naquin would become the tribe’s first leader.

More than a century and a half later, Albert Naquin envisioned ways to keep the tribe’s culture alive in a new home: There would be a tribal museum telling the stories of generations past, a grocery store like one on the island where the community gathered every Sunday after church, a space for holiday celebrations and a cultural classroom where younger generations could learn traditions like basket weaving and boatbuilding.

Then, in 2015, Louisiana applied for HUD’s National Disaster Resilience Competition, resulting in the $48 million grant to relocate Isle de Jean Charles residents.

In 2018, however, Naquin balked at the state’s handling of the resettlement project, saying it no longer ensured the culture and lifestyles of the community would survive because the state had co-opted the project and changed the original resettlement plan. Individual members of the tribe were allowed to make up their own minds about relocating, but Naquin decided against moving. “They wouldn’t let us in, they wouldn’t open the door for us,” he said.

Julie Maldonado, an anthropologist and lecturer on climate migration at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said tribal leaders, with their knowledge and expertise, should guide future relocation plans and decide what’s best for their communities. Often, she said, the government invites them to take a “seat at the table, but they built that table.”

Building a Framework for Climate Relocation

Pat Forbes, executive director of Louisiana’s Office of Community Development, acknowledges that the “New Isle,” 40 miles away on the former sugarcane field in Schriever, can’t replicate the island experience.

“I don’t want to create any illusion that we think we’re creating a better place to live,” he said. “All we’re doing is giving a second-best option, which is a safer place to live, that to the extent possible helps them start to revitalize their community.”

For four years, Jessica Simms, a policy analyst with the Office of Community Development, visited the island weekly to build trust in the resettlement process among island residents. She said OCD did “really extensive planning and outreach and wanted to ensure that we were able to capture what the residents wanted in their new homes.”

To date, 37 out of 42 families, some still on the island and others in temporary housing, have decided to move to the New Isle. Residents currently living on the Island are eligible to receive a home if they applied by Jan. 31, 2020, while past residents who were displaced from the island before Hurricane Isaac in 2012 will receive a lot, providing they demonstrate the financial ability to build a new home at the resettlement site, file an application by June 30, 2021 and sell their off-island homes. What remains of the 120 available lots will be offered to outsiders.

In meetings with the Office of Community Development, residents pushed for the right to retain ownership of their Isle de Jean Charles homes even if they relocate. But the homes cannot be their primary residences, they cannot rebuild them if they are damaged or destroyed by a hurricane and only minor repairs are allowed.

Tribal leaders worry that the community will have a hard time affording property taxes and home insurance on the new homes, expenses they haven’t had to pay on the island because of low property values. Those costs will be offset, according to OCD, by the energy-saving design of the new homes, as well as 10 years of subsidized homeowners and flood insurance.

Simms hopes that this effort can be replicated by other communities displaced by climate change. “What we’re trying to do here is build a framework so that there are other communities that can take what they want, what worked here, what didn’t work, the lessons learned,” she said.

Scientists predict that the sea will rise another six feet by the turn of the next century, due to melting glacial ice and warmer ocean temperatures.

“It’s already beginning to impact low-lying communities, particularly places outside the levee system,” said Kolker, the coastal geologist.

Nearby, the Pointe-au-Chien Tribe Adapts

Louisiana tribes along the bayou, including the Isle de Jean Charles Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw, United Houma Nation, Pointe-au-Chien and the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Indians, lack federal recognition they’ve been seeking for years. Among the most vulnerable to sea level rise, they are ineligible for federal assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

Four miles from Isle de Jean Charles, the Pointe-au-Chien tribe has learned to adapt to a sinking land even as some members contemplate resettlement. They have built a greenhouse to bring back medicinal plants that can’t grow because of saltwater, and installed a natural oyster bed to harden the shoreline and protect the land from coastal erosion.

The actions might not be enough to save the community. A category four storm could devastate their area and force the tribe to relocate, Chairman Chuckie Verdin said. But seeing what happened with tribal members on the Isle de Jean Charles, he’s afraid of not being in control of the resettlement process.

Theresa Dardar, a tribal member, isn’t giving up on the land just yet. There’s still time to divert sediment and rebuild land through tactics like canal backfilling, she said. But the government isn’t taking action. “Doesn’t matter what we say, I don’t think it’ll do any good. I think they listen with a closed mind,” Dardar said.

While tribes have tried to participate in creating Louisiana’s Coastal Master Plan, she said, they do not feel their input has been valued.

Shirell Parfait-Dardar, chief of the Grand Caillou/Dulac Band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Indians, who wants to relocate the tribe without government help, is going to use a proposal similar to that of Albert Naquin but will seek other avenues like nonprofits for funding.

“They clearly are following a system that does not understand us or even want to, that same system of assimilation. It needs to be in the hands of the communities and the tribes. We are the stewards of our environments, we are the ones that are responsible for our people’s well-being,” she said.

Parfait-Dardar said her tribal land will be gone in 25 to 50 years. “We’re gonna fight as long as there’s a piece of land left,” she said.

Tribes should have the right to stay or return to their ancestral lands even if threatened by climate change, said Maldonado, the University of California anthropologist, so that the relocation is not a continuation of past forced assimilation, removal or cultural genocide. “Even if a place becomes no longer permanently inhabitable, their livelihoods, their identities, their culture is directly connected to that place,” she said.

‘I Just Don’t Want This Place to be Erased’

Back on the Isle de Jean Charles, the Rev. Roch Naquin, 88, and members of his family struggle with letting go. For Naquin, the muskrats and mink he once trapped out back in the marsh, and the oak trees he cut for firewood, are memories now that tie him to the land without making him turn away from resettlement.

He said he feels optimistic about the process, in part because he’ll be living in a new home between those of a niece and a nephew. As a preacher, he’s encouraging others from the community to follow suit.

“I tried to tell them when I talk with them that while we have the opportunity to move to higher ground, that they should take advantage of it,” he said.

His nephew, Chris Brunet, 55, is the fifth generation of his family to grow up on the isle. He’s lived through many changes. Fifteen trees in his yard have vanished over the years. In 2003, worsening storms forced him to elevate his home.

“What they told me was this,” he said of family members. “‘Once the world was finished with you, you come back home; this is where you belong.’”

While he has a hard time imagining living anywhere else, Brunet said he recently decided that moving to the New Isle was the best choice for raising his niece and nephew. It will feature a community center, market, festival grounds and walking trails. The homes, which will be built 12 feet above sea level outside the 500-year floodplain, include screened porches and covered outdoor space and are located within a five-minute walk of a park, a bayou and a wetland area.

But some apprehension remains. Instead of being surrounded by water where he can go shrimping, crabbing or fishing, he’ll be in town, surrounded by businesses, neighborhoods and busy streets.

“Once I’m over there, there’ll always be something missing,” Brunet said.

He plans to return to the isle regularly and sit under his house to enjoy nature.

“I just don’t want this place to be erased,” Brunet said. “It is something that I feel truly blessed about having experienced.”